In boardrooms across the world there is a growing realisation that artificial intelligence is no longer a peripheral technology. It is embedded in strategy, operations and even customer interactions. The speed at which AI capabilities are evolving is breathtaking, yet many governance structures remain rooted in a pre-AI world. This gap between technological reality and governance maturity is now one of the most significant risks facing organisations.

The events of the past year have underscored that AI governance is not an abstract ideal but an urgent requirement. In August 2025, boards are finding themselves under pressure from regulators, investors, employees and the public to demonstrate that they can understand, oversee and guide the use of AI. The challenge is that governance without understanding is merely theatre. To govern AI effectively, boards and executives must first have a working grasp of its capabilities, its risks and its strategic implications.

Governance under pressure

Recent research shows a marked increase in the number of boards appointing directors with AI experience. Almost half of Fortune 100 companies now list AI expertise as a qualification, up from less than a quarter in 2024. Technology committees, once rare, are becoming more common. Yet Deloitte’s latest findings reveal that while AI is firmly on board agendas, 31 per cent of organisations still feel unprepared to deploy it effectively. The conversation is happening, but confidence and capability have yet to catch up.

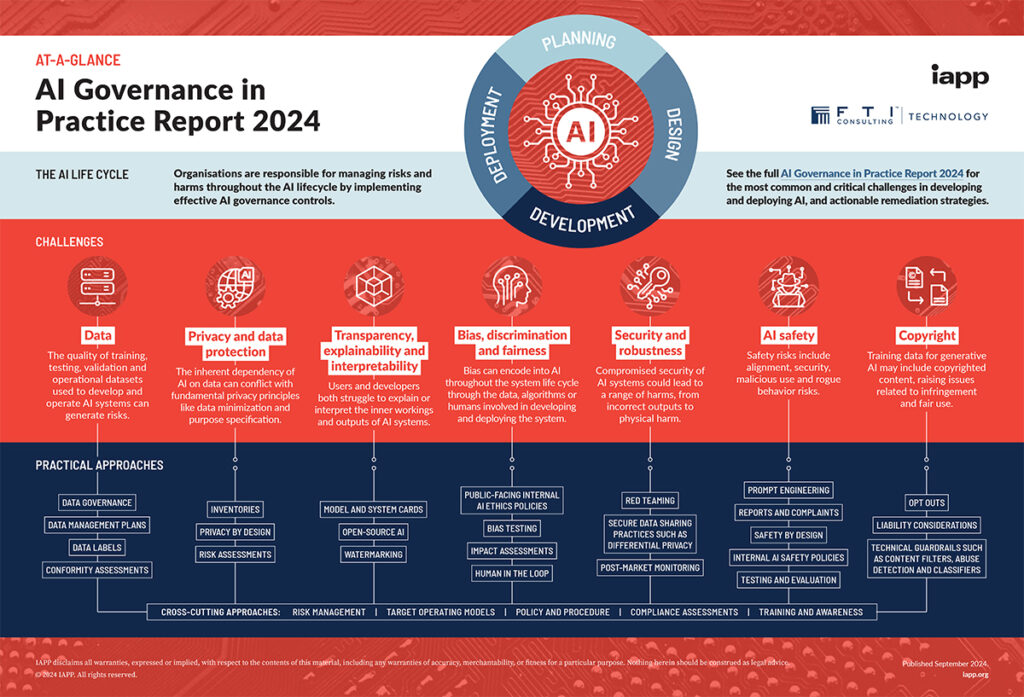

The urgency is being driven by three converging forces: the rapid growth in AI adoption, a steep rise in AI-related incidents, and an accelerating regulatory environment. Between 2022 and 2023, AI-related incidents grew by more than a quarter, and early indications suggest the growth rate into 2024 has been even higher. This is not just about spectacular failures. Many incidents are mundane but cumulative, involving bias in automated decision-making, privacy breaches or breaches of contractual obligations. The reputational damage, however, can be just as severe.

A fragmented but tightening regulatory landscape

Governance is not taking place in a vacuum. Regulators worldwide are moving from consultation to enforcement. In Europe, the Artificial Intelligence Act came into force in August 2024, establishing a risk-based framework that classifies AI systems according to their potential impact and mandates specific requirements for each risk level. It also created the European Artificial Intelligence Board to oversee implementation and compliance.

In parallel, the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention on AI has been adopted by more than fifty countries, embedding commitments to human rights, transparency and accountability into AI governance structures. In the United States, Executive Order 14110 now requires major federal agencies to appoint chief AI officers and directs the National Institute of Standards and Technology to strengthen its AI Risk Management Framework. At the state level, 48 states and Puerto Rico have introduced AI-related bills, with 26 having enacted legislation focusing on transparency, bias and child protection.

Australia, meanwhile, is engaged in a heated debate over intellectual property in the AI age. The Productivity Commission has proposed broad text and data-mining exemptions to train AI systems, prompting concern among creators and rights holders. The debate reflects a wider global tension between innovation and the rights of individuals and industries affected by AI development.

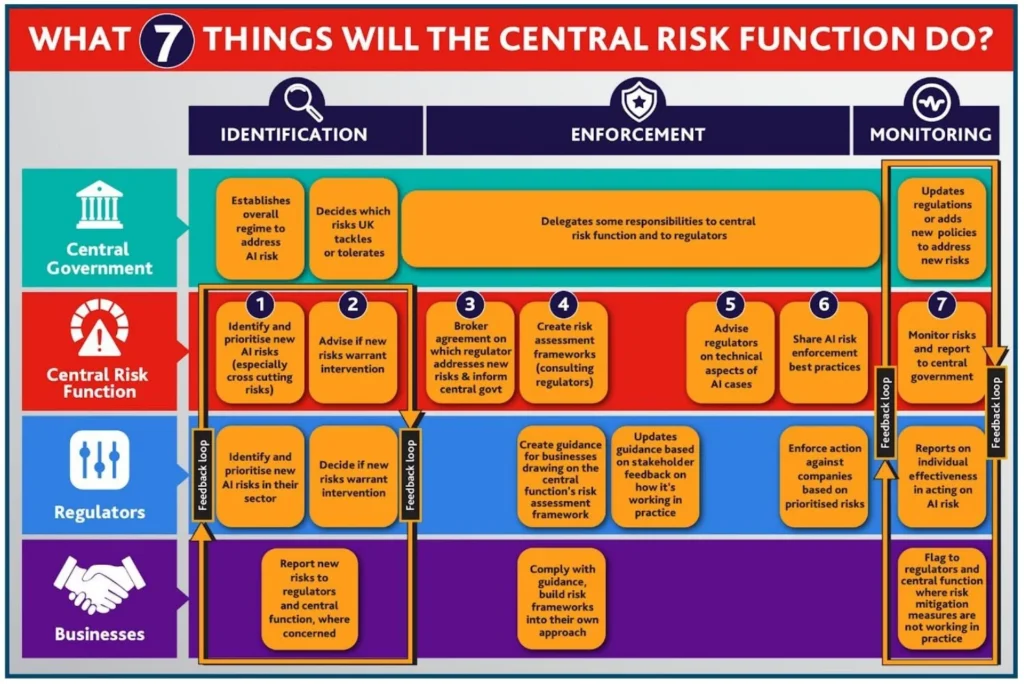

In the UK the stance remains distinct. The government continues to favour a pro‑innovation, principle‑based approach over detailed legislation. There is no general AI law, though existing regimes such as data protection and automated decision‑making rules do impose limits. The AI Safety Institute (now the AI Security Institute), launched following the 2023 AI Safety Summit, monitors frontier AI models and conducts safety evaluations. In January 2025 the government unveiled its AI Opportunities Action Plan, aiming to boost compute infrastructure, create AI Growth Zones, build a National Data Library and establish a UK Sovereign AI unit, all while maintaining regulatory light‑touch.

At the same time, consultations are under way regarding copyright reform to clarify the scope for AI developers. These measures suggest the UK is betting on institutional frameworks and strategic infrastructure rather than primary legislation or regulation. Whether that balance will hold against mounting security and ethical pressures amidst the pace of AI development remains to be seen.

Boards professionalising AI governance

In this evolving environment, boards are beginning to professionalise AI governance in the same way they did for cyber security over the past decade. The 2025 AI Governance Profession Report found that 77 per cent of organisations are actively building governance programmes for AI, and almost half consider it a top-five strategic priority. Even organisations that have not yet deployed AI rate governance readiness as a priority.

Some boards are creating dedicated AI oversight committees, while others are embedding AI risk into the remit of existing audit or risk committees. The underlying principle is the same: without formal structures and dedicated expertise, governance will be inconsistent and reactive.

Technical solutions to strengthen governance

The governance challenge is not purely a matter of policy. Technical frameworks and tools are emerging that can help boards translate governance principles into operational practice.

The Unified Compliance Framework (UCF) offers a comprehensive set of 42 controls unified across risk taxonomy and regulatory requirements. UCF can be mapped to GDPR, ISO 27001 and other EU data‑privacy and security standards, enabling streamlined compliance across member‑state regimes. This helps organisations manage controls efficiently, eliminate duplication and build a shared foundation for cross-jurisdictional oversight.

The Responsible AI Roadmap offers a blueprint for designing, deploying and governing AI systems that are trustworthy, auditable and accountable. It embeds ethical principles throughout the lifecycle of AI development and use, rather than treating them as a compliance afterthought.

For organisations operating internationally, blockchain-enabled compliance frameworks offer a way to ensure trust and traceability in AI governance across borders. By using decentralised ledgers to record decisions, data provenance and model changes, these frameworks aim to make compliance transparent and verifiable to stakeholders anywhere in the world.

What boards need to do now

Boards that wish to lead rather than follow on AI governance should take several immediate steps. First, they must invest in AI literacy at the board level. This does not mean turning directors into data scientists, but it does require a shared understanding of AI’s capabilities, limitations and risks.

Second, they should review whether governance structures are fit for purpose. This may involve establishing dedicated AI oversight bodies or ensuring existing committees have the remit and expertise to address AI risk.

Third, boards should explore technical governance tools that can make oversight more effective and efficient. Frameworks such as UCF and the Responsible AI Roadmap, coupled with transparent, auditable systems, can give boards confidence that governance is embedded throughout the organisation.

Finally, boards must remember that AI governance is not a one-off exercise. The pace of change in AI means governance will need to be dynamic, informed by constant learning and updated to reflect new risks and regulations.

The cost of inaction

The reality is simple: you cannot govern what you do not understand. AI offers immense opportunities, but without informed, modern governance it can expose organisations to unacceptable risk. Boards that fail to grasp this will find themselves outpaced not only by competitors but by regulators and the court of public opinion. Those that rise to the challenge, however, will not only protect their organisations but position them to thrive in the AI-driven economy.